Roosevelt's Diplomacy

"Speak softly and carry a big stick."

The Monroe Doctrine, put forth in 1823 by President James Monroe, called for an end to European intervention in the American continents (both north and south). This applied only to independent governments in the Americas however, not to areas that were colonies at that time.

In what came to be known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, Roosevelt asserted that European nations should not intervene in countries to the south of the US, however under certain conditions, United States intervention might be justified.

Roosevelt's Speech:

"There are certain essential points which must never be forgotten as regards the Monroe Doctrine. In the first place we must as a nation make it evident that we do not intend to treat it in any shape or way as an excuse for aggrandizement on our part at the expense of the republics to the south. We must recognize the fact that in some South American countries there has been much suspicion lest we should interpret the Monroe Doctrine as in some way inimical to their interests, and we must try to convince all the other nations of this continent once and for all that no just and orderly government has anything to fear from us. There are certain republics to the south of us which have already reached such a point of stability, order, and prosperity that they themselves, though as yet hardly consciously, are among the guarantors of this doctrine. These republics we now meet not only on a basis of entire equality, but in a spirit of frank and respectful friendship, which we hope is mutual. If all of the republics to the south of us will only grow as those to which I allude have already grown, all need for us to be especial champion of the doctrine will disappear, for no stable and growing American republic wishes to see some great non-American military power acquire territory in its neigborhood. All that this country desires is that the other republics on this continent shall be happy and prosperous; and they cannot be happy and prosperous unless they maintain order within their boundaries and behave with a just regard for their obligations toward outsiders. (Fifth Annual Message, Washington, December 5, 1905.) Mem. Ed. XVII, 352-353; Nat. Ed. XV, 301-30(Click here)

In what came to be known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, Roosevelt asserted that European nations should not intervene in countries to the south of the US, however under certain conditions, United States intervention might be justified.

Roosevelt's Speech:

"There are certain essential points which must never be forgotten as regards the Monroe Doctrine. In the first place we must as a nation make it evident that we do not intend to treat it in any shape or way as an excuse for aggrandizement on our part at the expense of the republics to the south. We must recognize the fact that in some South American countries there has been much suspicion lest we should interpret the Monroe Doctrine as in some way inimical to their interests, and we must try to convince all the other nations of this continent once and for all that no just and orderly government has anything to fear from us. There are certain republics to the south of us which have already reached such a point of stability, order, and prosperity that they themselves, though as yet hardly consciously, are among the guarantors of this doctrine. These republics we now meet not only on a basis of entire equality, but in a spirit of frank and respectful friendship, which we hope is mutual. If all of the republics to the south of us will only grow as those to which I allude have already grown, all need for us to be especial champion of the doctrine will disappear, for no stable and growing American republic wishes to see some great non-American military power acquire territory in its neigborhood. All that this country desires is that the other republics on this continent shall be happy and prosperous; and they cannot be happy and prosperous unless they maintain order within their boundaries and behave with a just regard for their obligations toward outsiders. (Fifth Annual Message, Washington, December 5, 1905.) Mem. Ed. XVII, 352-353; Nat. Ed. XV, 301-30(Click here)

Roosevelt Builds the Panama Canal

The popular acclaim that carried Teddy Roosevelt to the governorship of New York didn't stop there. In 1900, Republicans nominated Teddy as President McKinley's running mate. McKinley won a second term, and Teddy was sworn in as vice-president. Six months later, an assassin's bullet killed McKinley. At age 42, Theodore Roosevelt became the nation's youngest president. Roosevelt assumed the office with the same vigor with which he charged up Kettle Hill. A long believer in Captain Mahan's theory of sea power, Roosevelt began to revitalize the navy. Now that America's empire stretched from the Caribbean across the Pacific, the old idea of a canal between the two oceans took on new urgency. Mahan had predicted that "the canal will become a strategic center of the most vital importance," and Teddy agreed. "The canal," Roosevelt said, "was by far the most important action I took in foreign affairs during the time I was President. When nobody could or would exercise efficient authority, I exercised it."

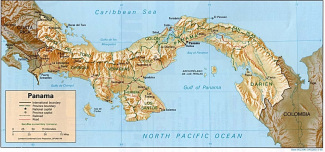

Joining the WatersIn 1878 Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French engineer who built the Suez Canal, began to dig a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, which was then part of Colombia. Tropical disease and engineering problems halted construction on the canal, but a French business (the New Panama Canal Company) still held the rights to the project. Roosevelt agreed to pay $40 million for the rights, and he began to negotiate with Colombia for control of the land. He offered $10 million for a fifty-mile strip across the isthmus. Colombia refused. "We were dealing with a government of irresponsible bandits," Roosevelt stormed. "I was prepared to . . . at once occupy the Isthmus anyhow, and proceed to dig the canal. But I deemed it likely that there would be a revolution in Panama soon."

Teddy was right. The chief engineer of the New Panama Canal Company organized a local revolt. Roosevelt immediately sent the battleship Nashville and a detachment of marines to Panama to support the new government. The rebels gladly accepted Roosevelt's $10 million offer, and they gave the United States complete control of a ten-mile wide canal zone. Roosevelt ordered army engineers to start digging. Thousands of workers sweated in the malarial heat. They tore up jungles and cut down mountains. Insects thrived in muddy, stagnant pools. "Mosquitoes get so thick you get a mouthful with every breath," a worker complained. The mosquitoes also carried yellow fever, and many fell victim to the deadly disease before Dr. William Gorgas found a way to stop it.

Some Americans did not approve of Roosevelt's behavior. "There was much accusation about my having acted in an 'unconstitutional' manner," Teddy shrugged. "I took the isthmus, started the canal, and then left Congress -- not to debate the canal, but to debate me. . . . While the debate goes on, the canal does too; and they are welcome to debate me as long as they wish, provided that we can go on with the canal." Work did go on. Despite lethal landslides, workers with dynamite and clumsy steam shovels cut their way across a continent. They built a railroad, three sets of concrete locks, and a huge artificial lake. Nine years later the freighter Ancon entered the new channel. Hundreds of construction workers hopped aboard for the historic ride. A shiny towing locomotive pulled the Ancon into the first lock. Bands played and crowds cheered as the ship slipped into the Pacific.

Roosevelt liked to repeat an old African saying: "Speak softly, and carry a big stick. You will go far." In Panama, Teddy proved to the world that he was willing to use his big navy as a stick to further American interests.

Joining the WatersIn 1878 Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French engineer who built the Suez Canal, began to dig a canal across the Isthmus of Panama, which was then part of Colombia. Tropical disease and engineering problems halted construction on the canal, but a French business (the New Panama Canal Company) still held the rights to the project. Roosevelt agreed to pay $40 million for the rights, and he began to negotiate with Colombia for control of the land. He offered $10 million for a fifty-mile strip across the isthmus. Colombia refused. "We were dealing with a government of irresponsible bandits," Roosevelt stormed. "I was prepared to . . . at once occupy the Isthmus anyhow, and proceed to dig the canal. But I deemed it likely that there would be a revolution in Panama soon."

Teddy was right. The chief engineer of the New Panama Canal Company organized a local revolt. Roosevelt immediately sent the battleship Nashville and a detachment of marines to Panama to support the new government. The rebels gladly accepted Roosevelt's $10 million offer, and they gave the United States complete control of a ten-mile wide canal zone. Roosevelt ordered army engineers to start digging. Thousands of workers sweated in the malarial heat. They tore up jungles and cut down mountains. Insects thrived in muddy, stagnant pools. "Mosquitoes get so thick you get a mouthful with every breath," a worker complained. The mosquitoes also carried yellow fever, and many fell victim to the deadly disease before Dr. William Gorgas found a way to stop it.

Some Americans did not approve of Roosevelt's behavior. "There was much accusation about my having acted in an 'unconstitutional' manner," Teddy shrugged. "I took the isthmus, started the canal, and then left Congress -- not to debate the canal, but to debate me. . . . While the debate goes on, the canal does too; and they are welcome to debate me as long as they wish, provided that we can go on with the canal." Work did go on. Despite lethal landslides, workers with dynamite and clumsy steam shovels cut their way across a continent. They built a railroad, three sets of concrete locks, and a huge artificial lake. Nine years later the freighter Ancon entered the new channel. Hundreds of construction workers hopped aboard for the historic ride. A shiny towing locomotive pulled the Ancon into the first lock. Bands played and crowds cheered as the ship slipped into the Pacific.

Roosevelt liked to repeat an old African saying: "Speak softly, and carry a big stick. You will go far." In Panama, Teddy proved to the world that he was willing to use his big navy as a stick to further American interests.